Starbuck Means More Than Java in Fresno

by John Edward Powell

Starbuck. The name resonates with familiarity. For young Americans coming of age during the 1990s, Starbuck is a behavioral trademark indelibly etched in the social iconography and lexicon of sipping cappucino at curbside cafes. A mere decade ago, however, aficionados of science fiction recognized Starbuck as a swashbuckling character popularized by the imaginative special-effects wizardry of television's Battlestar Galactica. More than a century earlier, Chief Mate Starbuck strode the decks of the Pequod in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick. Starbuck is a word that rings true of epic tradition.

Imbued in our fictional memory with mythological allusion and muscular intensity, the Starbuck moniker is in reality no less colorfully rooted in our earliest American history. To scholars of the colonial past, it recalls the first settlements on Nantucket Island during the 1600s, and the great shipping enterprises that subsequently set sail from Massachusetts. In nineteenth-century Boston, it is identified with the celebrated architecture of this most historic of our nation's cities.

Forged on the east coast, and long buried in the annals of American architecture, the Starbuck lineage likewise figures squarely in California regionalism as the result of the architectural migration of Henry F. Starbuck. Quite dramatically, a vital link in this end-of-the-century westward saga is preserved in Fresno, California.

Henry F. Starbuck was born of Portuguese ancestry in Nantucket,

Massachusetts, on March 1, 1850. His father, Henry J. Starbuck, came to America

as a cabin boy on a whaling ship from the Azores and later became a whaling

captain, skippering the ships Franklin and Daniel Webster. The

youngest of four children, Henry F. Starbuck completed his education in Boston

and fulfilled his apprenticeship there under Harvard-educated architect Abel C.

Martin (1831-1879). Starbuck formed his first partnership in Boston with George

A. Moore as Moore & Starbuck Architects in 1873, followed by a partnership

with Arthur H. Vinal as Starbuck & Vinal in 1877. That same year he

established an office in New Brunswick, where he designed the Bank of New

Brunswick and other fine buildings. Two years later he abandoned his eastern

practice and moved to Chicago, where he initially specialized in engineering

projects incorporating refrigeration and heavy machinery.

Henry F. Starbuck was born of Portuguese ancestry in Nantucket,

Massachusetts, on March 1, 1850. His father, Henry J. Starbuck, came to America

as a cabin boy on a whaling ship from the Azores and later became a whaling

captain, skippering the ships Franklin and Daniel Webster. The

youngest of four children, Henry F. Starbuck completed his education in Boston

and fulfilled his apprenticeship there under Harvard-educated architect Abel C.

Martin (1831-1879). Starbuck formed his first partnership in Boston with George

A. Moore as Moore & Starbuck Architects in 1873, followed by a partnership

with Arthur H. Vinal as Starbuck & Vinal in 1877. That same year he

established an office in New Brunswick, where he designed the Bank of New

Brunswick and other fine buildings. Two years later he abandoned his eastern

practice and moved to Chicago, where he initially specialized in engineering

projects incorporating refrigeration and heavy machinery.

By 1886, Starbuck had returned to the practice of architecture with offices in Chicago's Ashland Block. Among his major commissions during this period was the five-hundred-seat Trinity Episcopal Church in Michigan City, Indiana--an exquisite rock-faced American Romanesque design of Bedford stone. This and his design for a Methodist-Episcopal Church in Maine appear to be precursors to other commissions that later solidified his reputation as a church architect in California.

From Chicago Starbuck moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he entered into a partnership with Thomas Leslie Rose FAIA (1867-1935) as Starbuck & Rose Architects. Among his projects during this period was the Congregational Church in Baraboo, Wisconsin (1896). Upon dissolution of this partnership, Rose joined Charles Kirchoff and became an influential theater architect in the Midwest.

Starbuck, meanwhile, moved west where he first established a practice in San Diego by 1894. His earliest known California projects were an Episcopal church in El Cajon and a design proposal for a new high school in Fresno, although he did not receive the commission for the latter structure. Several of his early residential projects in San Diego received statewide press, including homes for Dr. S. E. Winn and Charles Low, followed by a design for the B. C. Lockwood Cottage during a short-lived partnership under the firm name of Starbuck & Logan.

By 1896, Starbuck had moved to Los Angeles, where he continued to gain prestige as a designer of churches. In 1899, he moved his office to Long Beach. Among his projects during this period were a Methodist-Episcopal church in Long Beach, a Baptist church in Los Angeles and the Knox Presbyterian church, also in Los Angeles.

In 1902, still practicing in Southern California, Starbuck designed a new structure in the Mission style for the Methodist-Episcopal Church in Fresno. He designed another Methodist-Episcopal Church in Bakersfield in 1903. Shortly thereafter Starbuck relocated to Oakland. He continued pursuing commissions in the San Joaquin Valley after this move, including his proposal for a Fresno County Almshouse in 1906. While practicing in Oakland, Starbuck formed a brief partnership with William Wilde, with whom he appears to have begun his design for a Fresno Masonic Lodge building in 1910.

Starbuck's work in the East Bay received wide publicity in the chief regional journal of the day, Architect and Engineer of California, for which he served as a "contributor." Among mentions of his work in this periodical were several articles descriptive of his Mission-style Oakland home. Interior photographic views of the house were profiled in a 1908 issue that also featured Craftsman designs by Greene & Greene of Pasadena.

Starbuck also authored several articles in Architect and Engineer, including a piece in 1905 entitled "Architecture of Masonic and other Fraternal Buildings." Renderings of his Masonic Lodges in Palo Alto and Santa Rosa were reproduced in the October and November 1905 issues. A 1910 piece entitled "Designs for Country School Houses" was nicely illustrated with Starbuck sketches and plans.

At age 60, Starbuck moved to Fresno following the grisly murder of tenants living at his Cazadero Ranch near Santa Rosa. Starbuck's wife, Margaret, a wealthy widow from Virginia whom he had married in Los Angeles in 1901, was widely known to be enamored with spiritualism. She operated the ranch which she "planned to use . . . as the foundation of a new cult" and develop as the site of a "temple . . . for all religions." Margaret was eventually implicated in the murder case for obstruction of justice, thrusting the Starbuck name into Bay Area newspaper headlines. Perhaps as the result of this negative press, followed by an equally well-publicized divorce, Starbuck gave up his flourishing practice in Oakland to seek "architectural exile" in Fresno, where he resettled to rebuild his career and life in 1910.

Once

in Fresno, Starbuck took on Alfred W. Clark (1879-1914) as his partner.

Together they aggressively launched a new architectural practice. Starbuck

& Clark designed numerous projects, including a residence for Maud I.

Pettus (1911), a charming shingle bungalow for Dr. George Hopkins (1911), a

Reedley ranch house for A. A. Brigstocke (1911), two houses for R. A. Pickford

(1911), an exotic Japanesque style bungalow for J. D. Stephens (1912), the J.

H. Craycroft Residence (1912), the Paul Frohberg Residence (1912), a Fowler

home for M. L. Harris (1912), the wonderfully whimsical Woodman of the World

Building (1912), the Eagles Lodge (1912), the Riverside Country Club (1912),

the Jacob Richter Building (1912), proposed plans for both the Sample

Sanitarium (1912) and the Whittmore Theater (1913), and the F. H. Wilson

residence (1913) in Dinuba. During the same period, but apparently working

independently of Clark, Starbuck designed a new building for the First

Congregational Church of Fresno in 1912 (shown on right). Still

standing, this Craftsman-style church is noted for its characterful witch's hat

tower.

Once

in Fresno, Starbuck took on Alfred W. Clark (1879-1914) as his partner.

Together they aggressively launched a new architectural practice. Starbuck

& Clark designed numerous projects, including a residence for Maud I.

Pettus (1911), a charming shingle bungalow for Dr. George Hopkins (1911), a

Reedley ranch house for A. A. Brigstocke (1911), two houses for R. A. Pickford

(1911), an exotic Japanesque style bungalow for J. D. Stephens (1912), the J.

H. Craycroft Residence (1912), the Paul Frohberg Residence (1912), a Fowler

home for M. L. Harris (1912), the wonderfully whimsical Woodman of the World

Building (1912), the Eagles Lodge (1912), the Riverside Country Club (1912),

the Jacob Richter Building (1912), proposed plans for both the Sample

Sanitarium (1912) and the Whittmore Theater (1913), and the F. H. Wilson

residence (1913) in Dinuba. During the same period, but apparently working

independently of Clark, Starbuck designed a new building for the First

Congregational Church of Fresno in 1912 (shown on right). Still

standing, this Craftsman-style church is noted for its characterful witch's hat

tower.

In 1913, the congregation of Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church announced a competition for the design of a new sanctuary building to be constructed at the corner of Ventura and M in Fresno. A young Armenian architect named Lawrence K. Condrajian (1888-1984) was at that time working in Henry Starbuck's office. Condrajian suggested to Starbuck that they go after the project together, but Starbuck encouraged Condrajian to prepare the design himself, thus launching Condrajian's solo career. Interviewed on April 20, 1982, at age 94, Condrajian characterized Henry Starbuck as a kind and generous man who did not share the common prejudice of the day against Armenians held by other "Anglo" architects in Fresno.

By 1914,

Starbuck found himself again working alone after Clark's untimely death at the

age of thirty-five. Nonetheless, for another decade Starbuck continued to

secure prestigious commissions, including the 1917 mansion for the Wylie M.

Giffen Estate in southeast rural Fresno (shown on left), now part of the

Fresno Pacific University campus.

By 1914,

Starbuck found himself again working alone after Clark's untimely death at the

age of thirty-five. Nonetheless, for another decade Starbuck continued to

secure prestigious commissions, including the 1917 mansion for the Wylie M.

Giffen Estate in southeast rural Fresno (shown on left), now part of the

Fresno Pacific University campus.

By the time he semi-retired to Los Angeles in 1926, at the

age of 76, Henry Starbuck had dotted the Central Valley horizon with a long

list of churches, including the Madera Presbyterian Church (1914), the Clovis

Presbyterian Church (1914), the

Henry F.

Starbuck died on August 21, 1935, at age 85, at the Masonic Home in Decoto,

California. With modern architecture in vogue, few acknowledged the death of

this senior member of traditional architecture's old guard. During the decade

and a half that he worked in the Central Valley, he created an impressive body

of work after already accomplishing what would have been for most architects a

full and distinguished career. Many of his buildings in and around Fresno still

stand, adding to a skyline admired with renewed curiosity because a national

passion for espresso has reprised the Starbuck name.

Henry F.

Starbuck died on August 21, 1935, at age 85, at the Masonic Home in Decoto,

California. With modern architecture in vogue, few acknowledged the death of

this senior member of traditional architecture's old guard. During the decade

and a half that he worked in the Central Valley, he created an impressive body

of work after already accomplishing what would have been for most architects a

full and distinguished career. Many of his buildings in and around Fresno still

stand, adding to a skyline admired with renewed curiosity because a national

passion for espresso has reprised the Starbuck name.

Architectural historian John Edward Powell, who completed this study while on sabbatical on the Central Coast in 1995, began his research on Henry F. Starbuck with grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the American Architectural Foundation.

©1995 John Edward Powell.

Photo of Giffen Home

courtesy of Fresno Pacific University Archives.

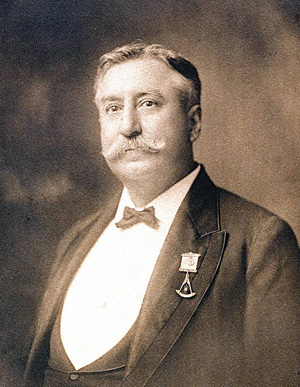

Photo of Henry F. Starbuck

courtesy of the Lytton Family.