by John Edward Powell

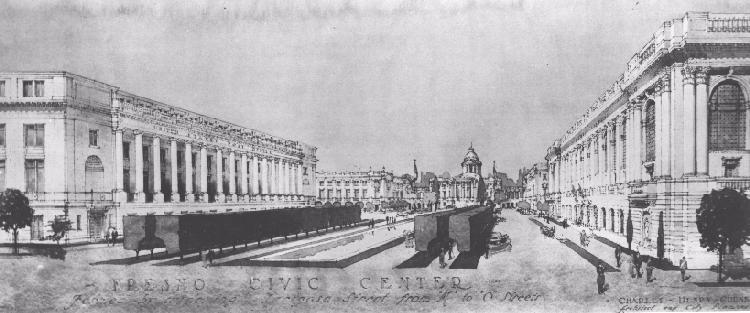

Since 1918, a visionary Civic Center Master Plan by the French-trained architect and planner Charles Henry Cheney has remained at the core of a slow evolution of municipal building expansion in Fresno's Civic Center. Challenged almost immediately, Cheney's City Beautiful plan, with a long, tree-lined plaza flanked by classically imposing government buildings (see below), remains a historic model to be reevaluated for the lessons it teaches. That plan's fate was to be a chronicle of lost opportunities to give Fresno the strong symbolic center it has always needed.

The Cheney Plan was treated from the beginning as an idea on paper, to be kept "on file until financial conditions [justified] the erection of buildings." No less a world authority than the Scot-born Canadian town planner Thomas Adams (a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects) visited Fresno in 1920 to study Cheney's nationally-published proposal. While praising Cheney's work, Adams, "urged that as prospects for Fresno future growth [were] unlimited the center [should] be developed on a more comprehensive scale." Adams encouraged the reluctant City to move ahead, calling to its attention his slight disfavor with Cheney's choice of classically-inspired architectural styles. Adams preferred an architecture that would have reflected the characteristics of regional traditions over European models. Following Adams' visit, a full year would pass before a citizens group actively took up the cause to promote Cheney's plan.

In 1921 the Fresno Rotary Club organized an effort to "crystallize public sentiment" to nudge a still-reluctant Board of Supervisors to begin construction on what Rotarians called "the first unit" of a master plan that would "place Fresno on a basis with other great cities of the world." Regrettably, the effort failed, and as one prominent Rotarian noted, "Fresno has satisfied herself in not looking into the future."

Cheney's plan again became the focus of debate in 1922, when the Grand Jury took the lead supporting a proposal by Eugene Mathewson to implement the first phase of building expansion based on Cheney's recommendations. Seven local architects immediately intervened by calling for a city policy guaranteeing that competition guidelines developed by the American Institute of Architects be followed for the selection of any architects hired to design the public buildings outlined in Cheney's plan. This dissenting move effectively stopped Mathewson's unilateral proposal, but likewise short-circuited the momentum to launch the master plan project at that time.

Nine years later, in 1931, Charles Butner and H. Rafael Lake joined architectural talents to propose a scaled-down version of the Cheney concept. Adams' earlier call for the plan's expansion fell to the realities of massive unemployment during the Depression. Voters rejected a bond issue that would have financed the Butner/Lake plan, after outspoken local landowners mounted a successful campaign to defeat it at the polls. Nonetheless, the idea of public-supported building projects to provide jobs got a boost from this modified proposal.

Two other plans would meet similar fates in 1933. The first proposal was devised by Fred L. Swartz, only to be followed three days later by another from H. Rafael Lake. Swartz broke precedent with the Cheney Plan by proposing that new municipal buildings be built outside Cheney's tightly-drawn perimeter line. Lake countered with a bare-bones recommendation that all City and County buildings be placed on the same block with the Court House. He reasoned that his plan "would keep the public buildings in close proximity to the business district," thereby saving "the probably excessive cost of acquiring additional property," as Cheney's plan required. The issue of land acquisition and siting was at this time fifteen years old, and a difficult hurdle to overcome in the absence of strong civic leadership. Neither the Swartz nor Lake plans succeeded.

Several more recent civic center master plans have been commissioned, but none has ever been fully implemented. The plans for the most part have been concepts to ignore. Many public structures that Cheney had proposed in 1918 were indeed built by PWA programs during the 1930s and 1940s. Expeditiously sited on the whole, but with little formal relationship between them, the structures nonetheless make up a significant collection of Moderne and Early Modern Style buildings. Among them, of course, is Franklin and Kump's 1941 City Hall, the only Fresno building to be included in the permanent architectural collection of New York's Museum of Modern Art. An earlier work in the PWA group, the Old School Administration Building, was also designed by Franklin and Kump and remains a classic example of the Dutch Modern Style found nowhere else in California. The State and Federal buildings that followed years later were uninspired additions to the basic Cheney footprint. Their inexpressive facades rose to terminate what Cheney had dreamed would be a magestic architectural finale to his sweeping landscaped axis.

Charles Henry Cheney's dramatic proposal for the siting of public buildings along the perimeter of a grand open space succumbed to years of inadequate civic leadership. The result today is an assortment of municipal buildings, some with immense architectural value, and others with minimal architectural character. Each has some proximity to a large undeveloped parcel, incongruously called Eaton Plaza, which is improperly utilized for surface parking. For the most part these buildings have been haphazardly "planted," without any architectural or landscape element having ever been implemented over the ensuing years to somehow unify an imperfect situation in some thoughtful manner.

This article was excerpted and adapted from a letter by John Edward Powell to the Fresno City Council, 13 October 1986. The Council was at that time selecting an architect to design a new City Hall, and Powell urged them to take Cheney's original plan into consideration when doing so. He encouraged the Council to "recapture in a fresh new plan something of the formal spirit which Charles Henry Cheney envisioned as the unifying element linking over a dozen government buildings." While the new City Hall as eventually completed looks like nothing that Cheney could have imagined, it does complete the eastern end of the Civic Center in the grand way that Cheney proposed.

© 1986 John Edward Powell